What is a word?

Words and morphemes in English grammar

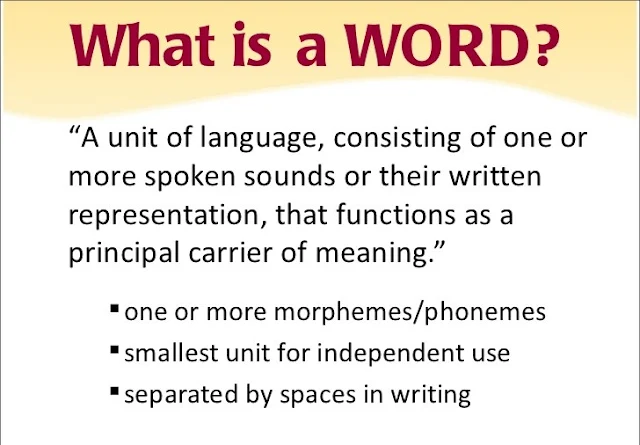

What is a word?

What precisely is a word? At first glance you may find it easy to find many examples of what would unambiguously constitute a 'word', for instance: you, the, those, some, hers, them, luck, irritation, large, conspicuously, hide, chemical, preference, of, at, from and similar examples.

Are these English words?

• dilly-dally

• rose-tinted

• eavesdropper

• glockenspiel

• splendiferous

• supacalifragilisticexpialidocious

If I were to say The girl over there is frakusiling with the gambanger could you replace any words

you don't know there with other words of a similar type? Does that make the words you replacedwords?

Are all the words in this sentence acceptable? Applying a stochastic production frontier to sector-level data, this paper examines the extent to which industrial countries' R&D contributes to East Asian economies' TFP growth.

What about this one? Hence, our analysis addresses foreign technology spillovers as sources of TP in an endogenous framework in addition to autonomous enhancement captured by the time trend as formulated by neoclassical theory.

Once we start to think about words seriously, things don't look so clear!

Let's think for a moment about how words are put together. There are two major ways:

1. Inflection

As soon as a new word comes into current use, it invariably takes over a whole range of other forms.

• microbe microbes

• house houses

• large larger largest

• fit fitter fittest

• (to) progress progresses progressed progressing

• qualify qualifies qualified qualifying

2. Word formation

Words can be joined in a number of different ways.

• foot + ball = football

• fox + trot = foxtrot

• ham + burger = hamburger

• dress + maker = dressmaker

• house + husband = house-husband

• hyper + inflation = hyper-inflation

• in + flexible = inflexible

The last example uses the word in to mean the opposite of the main noun. This is a very common way to produce a meaning that is the opposite of the base word.

• in + excusable = inexcusable

• in + vertebrate = invertebrate

• in + experienced = inexperienced

There are a very large range of these additions. When they are at the front of a word, they are called prefixes. When they are at the end of a word, they are called suffixes. Here are some examples of prefixes:

• defrost, defuse, deskill

• disapprove, disappear, dislike

• downsize, downturn, downtrodden

• endanger, enslave, enrich

• extraordinary, extra-curricular, extravagant

• handbag, handkerchief, hand-held

• improbable, impenetrable, imperfection

• illegitimate, illegible, illiterate

• lowlife, low-grade, low-level

• midnight , mid-term, mid-life

• misunderstood, misjudge, misplace

• newsworthy, newspaper, newsagent

• off-shoot, off-hand, off-colour

• outside, outrun, outclass

• post-war, post-haste, posthumous

• reply, recover, re-site

• unfair, unkind, unhealthy

• There are just as many suffixes, if not more! Here are some of them:

• American, Mexican, Tanzanian

• alcoholic, workaholic, chocoholic,

• freedom, stardom, kingdom

• audible, flexible, visible

• breakdown, splashdown, comedown

• carefree, interest-free, rent-free

• clearly, sweetly, smoothly

• fattish, lightish, boyish

• hostess, authoress, stewardess (note: these are less common today)

• largest, smallest, fattest

• manhood, priesthood, brotherhood

• management, employment, development

• muddle-headed, cool-headed, curly-headed

• pregnancy, fluency, clemency

• readable, dependable, portable

• snowbound, outward-bound, housebound

• started, ended, tumbled

• tradecraft, witchcraft, stagecraft

• trainee, trustee, employee

• Watergate, Irangate, Blairgate (Note: a fairly new addition to the language)

• weakness, lightness, kindness

How many other prefixes and suffixes can you think of?

But we not only add prefixes and suffixes, we also take things away. Think about the original words:

• auto

• bus

• demo

• fridge

• lab

• phone

• piano

• pram

• TV

Just for good luck, we also make names into everyday words ( Hoover ), we borrow from other languages (bungalow from Hindi) we join things together because they sound neat (easy-peasy) and if we can't do anything else, we just sit down and make up a new word (Internet).

Putting words together

Now that we have the more useful notion of what a word is, we can move on to consider in what ways words occur together to create longer stretches of language. One common view of language is that, as a text develops, at any point the speaker or writer is free to select whatever lexical item he or she desires, provided that the item conforms to the grammar rules of English. This has been called the 'open choice principle', where, following a grammatical unit - a clause, phrase or 'word' - a wide range of options is available to the speaker/writer. However, this cannot be true for English. In fact, many words attract options from a very limited list. This tendency for certain lexical items to appear together (co-occur) is called collocation and the l

No comments